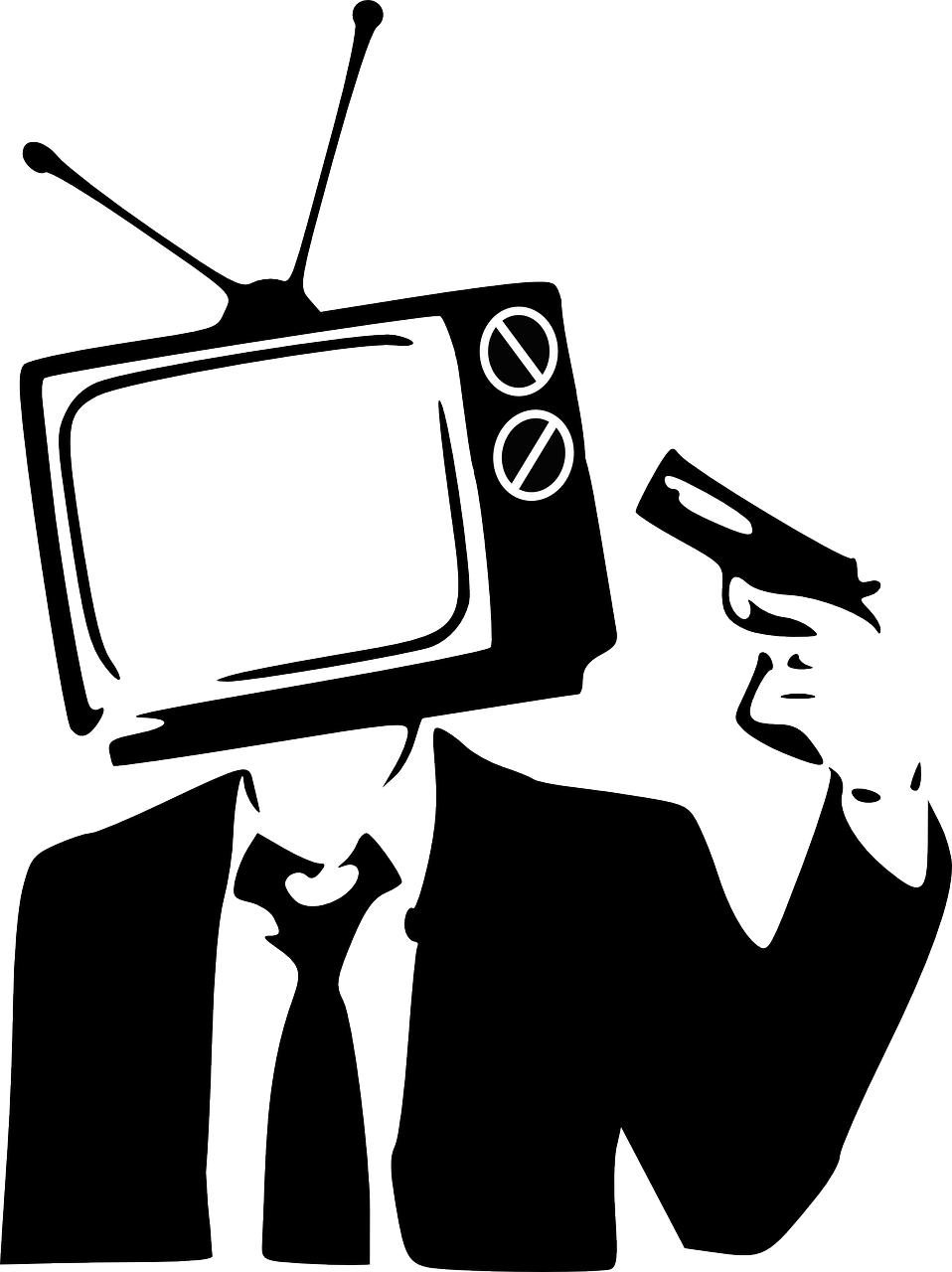

One TV to bring them all and in the darkness bind them

With so many trackers in our homes, why are TV manufacturers now spying on us, too?

I’m not sure why adding Internet connectivity to a device suddenly qualifies it as a “smart” device, but here we are. While some manufacturers still naively make the best product they can and enhance it by adding useful internet access, most of these devices are really Trojan horses designed to be attractive enough to get into our houses, and then blend into the background.

There they sit, forgotten, until some catastrophe like a new wifi router or power outage causes us to pay brief attention to them again. But, until then they silently sit in plain view, listening and watching, harvesting our daily lives for every tiny scrap of information they can sense, squirrelling it away for some future, coveting it against the time when it may be useful. How did we get here? Believe it or not, it’s all about advertising.

“This is too hard, let’s just get them to tell us what they want” — Google

The quest for better ways to determine consumer wants is as old as consumer wants. It has been going on since Grog tried an A/B test at the market with a round and not-quite-so-round stone wheel. We all know how that turned out, but it’s not so easy for today’s advertisers.

A few years before Dexter started high school (more on him later), things were pretty tough for advertisers. In fact, nothing much changed before 1998. Advertisers would have to work off small subsets of consumer data, hoping that it would reliably scale to mass markets. The best known data collector is the Neilsen Corporation . That’s the company that put trackers on (willing) consumer’s TV sets to record what they watched and those families controlled what everyone watched for decades and, to some extent, still do today.

In the early 90s internet became widely available but it was hard to find anything good despite early search engines like Alta Vista. In 1998 two guys at Stanford envisioned a new kind of search engine. At the time, existing search engines would determine the value of a page against a search term by the amount of times the search term occurred in that page. Obviously, that is a very flawed system that allows website owners to game the system to get higher up on the search results page. Sergey Brin and Larry Page figured that the real value of a page is how many other sites link to it, thus inventing the idea of PageRank and Google was born.

Brin and Page had cracked the advertising nut. The best way to find out what consumers want is to just get them to wander on up and tell you. What’s the best way to do that without actually doing that and being creepy? Create a really good search engine that millions upon millions of people will use and type in their deepest darkest desires to take all the guess work out of what people want.

Just one short year later in 1999 Google started selling advertising and went on to become one of the first companies to hit a trillion dollars in market capitalization. Remember those small subsets of data advertisers used to have to work off? Nobody does because Big Data had been born.

“You’re painting a masterpiece, make sure to hide the brush strokes“ — Betty Draper

Having people willingly give up their desires into a search engine was revolutionary and extremely successful, but it was still just a subset of all the wants and desires in the world. What about those people who weren’t searching for stuff right now? What do they want? How do we sell ads to them?

Advertising is so lucrative that companies that had nothing to do with content a mere few years ago have now twisted their devices into persistent want collectors. Amazon, Google, and — to a lesser extent — Facebook were the first into the fray with their clumsy microphone things. They outright told us that these were microphones that would be listening to us, but the real trick was convincing us that we were getting the real benefit. The ability to just yell out “What’s the weather? When should I leave for work? Play my booty call mix!” to make things happen was so valuable that we agreed to let these companies listen to every conversation about our medical stuff, our finances, our children’s phone calls, the whole kingdom. At least with the search engine trick we got some value out of it — we (usually) found the information we were looking for. Trading every ounce of our personal privacy to turn on a light bulb with our voice is a whole new type of masterpiece.

However, in the end, this still has too much friction. As more articles are written about how these companies use our data, and as we watch CEOs from these companies get called to defend themselves in the US Congress, doubts start to rise and confidence wanes. We need to go back to the Google model where people just tell us what they want without all the friction of convincing them to deliberately put a microphone in their house. Begin Phase Two.

“Phase two is like phase one, but more evil” — Jon Watson

I wish I was there that day. The day that person was moping about in Starbucks, dismayed at the combination of a great table, but terrible wifi; desperately struggling to come up with one good idea that day to stave off an ever declining ad revenue stream and suddenly, it was born.

Dexter (maybe his real name?) bolted upright then paused. His eyes faded into that faraway look for few minutes, lip quivering a bit, wondering if the idea really had any legs. He glanced down at his phone, and picked it up with shaking hands. Still unsure, he put it back down, sat back for a second and sipped his triple thingy, before slamming the coffee back down and grabbing the phone from the table.

Visibly shaking he texted Sharon (maybe her real name?) “What if….Orwell, what if we did that Orwell thing?” He sat back, eyes riveted to the screen, waiting. Finally, the dots started dancing and the response came back “Don’t be an idiot, nobody is going to let TVs spy on them. Where’s my coffee??”. Enraged, Dexter jumped to his feet and yelled “Screw you, Sharon!” and called Samsung. Samsung liked the idea. Starbucks did not and kicked Dexter to the curb.

“One TV to bring them all and in the darkness bind them” — Samsung

The stage is set. We have reliable, ubiquitous internet. We have consumers who are comfortable with having many devices around the house. We have consumers who like television. Let’s do this!

I’m unfairly picking on Samsung because the front runner in the game of secretly recording consumers without their knowledge goes to Vizio, a company nobody has ever heard of. Vizio’s TVs led the field in spying on customers by collecting what they were watching and then selling that data to advertisers. Which, arguably, might be OK if said users knew it was happening, but they did not and Vizio got slapped with a multi-million dollar law suit for its shenanigans.

But Samsung, LG, and other TV manufacturers were not far behind in sending data about what is on your screen to other parties. In some cases, the data isn’t even being sent to the TV manufacturer. Rather, it is being sent to…you guessed it…those guys who have been trying to convince us to put microphones in our homes for years— Google, Facebook, and more surprisingly, Netflix.

the team said that 34,586 controlled experiments revealed a total of 71 out of 81 devices send information to destinations other than the device manufacturer;

Why do TV manufacturer’s bother to do this? Almost everything we watch is already delivered over the internet and is therefore tracked to the last second anyhow. Even so-called “traditional cable TV” is typically IPTV that is delivered over the internet and we change “channels” by leaving one VLAN and joining another. Not a single click goes unnoticed by the purveyor of our viewing passions. But there’s a wrinkle — we need to bind them.

Let’s talk silos. Netflix knows what its customers are watching. Amazon knows what its Prime users are watching. Crunchy Roll knows your Anime weirdness, but none of them know what the others’ customers are watching. Only the TV set knows and that, dear reader, is the point. Tech companies that used to be satisfied with making the next awesome looking screen out of pride, now do so only to ensure you buy their TV so that they are the lucky ones to collect your data and sell it out the back door to multiply their riches.

Taken one step farther, what about the TV that nobody provides? No matter how many services we have in our homes, we can watch DVDs and thumb drives, and torrented stuff with impunity. Until now. Now Samsung and LG and Vizio even know when you’re watching that old ahem VHS tape from college because the TV doesn’t care where the content came from, it just sends whatever is on the screen back to the mother ship.

Can you stop this? In theory, yes — some governments require television manufacturers to provide a way to opt out. But in practice, your mileage may vary.

my shorter content on the fediverse: https://cosocial.ca/@jonw